In the early days, decision-making was non-stop. They compared daily sales to daily targets, changing tactics immediately and often, repeatedly opting for actions with instantaneous feedback via data.

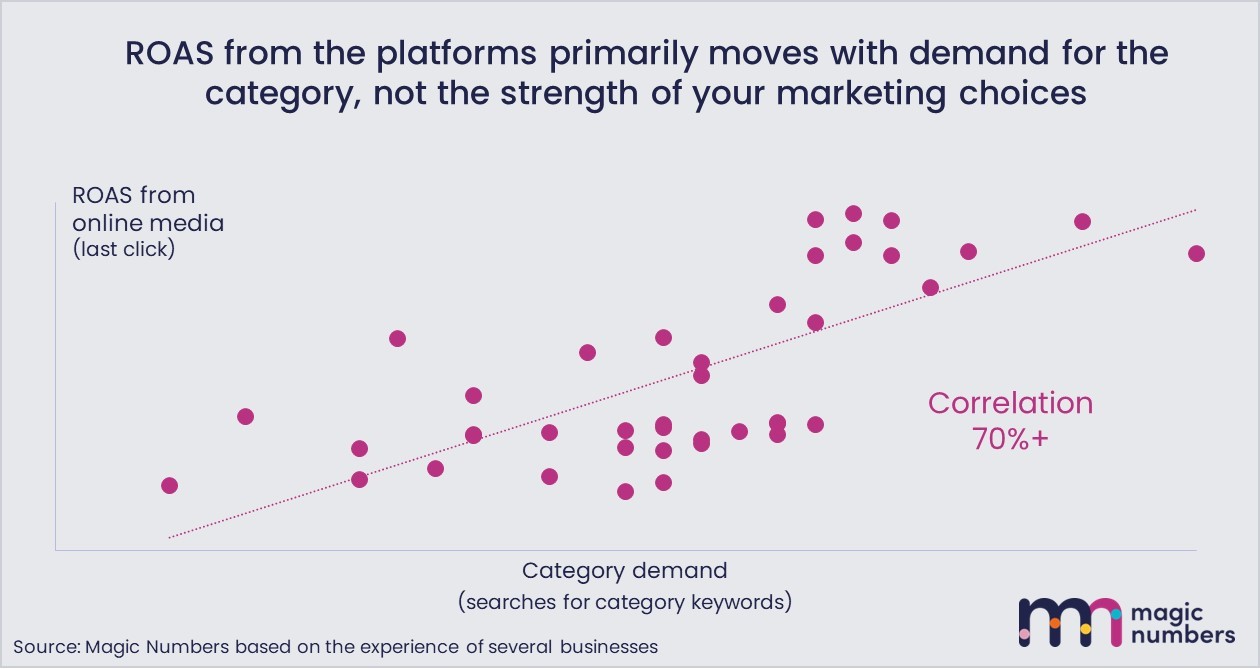

In advertising, they used data on clicks, conversions and ROAS to decide on everything from creative to messaging, media allocation, and how much to spend.

And they managed price this way too. If sales weren’t where they should be, they offered discounts wherever data said they’d get the best response.

Even though each individual decision looked right, away from the dashboards more and more of their sales went through on deal. And their marketing was dizzyingly changeable, they had more than 20 completely different campaign ideas in just 2 years.

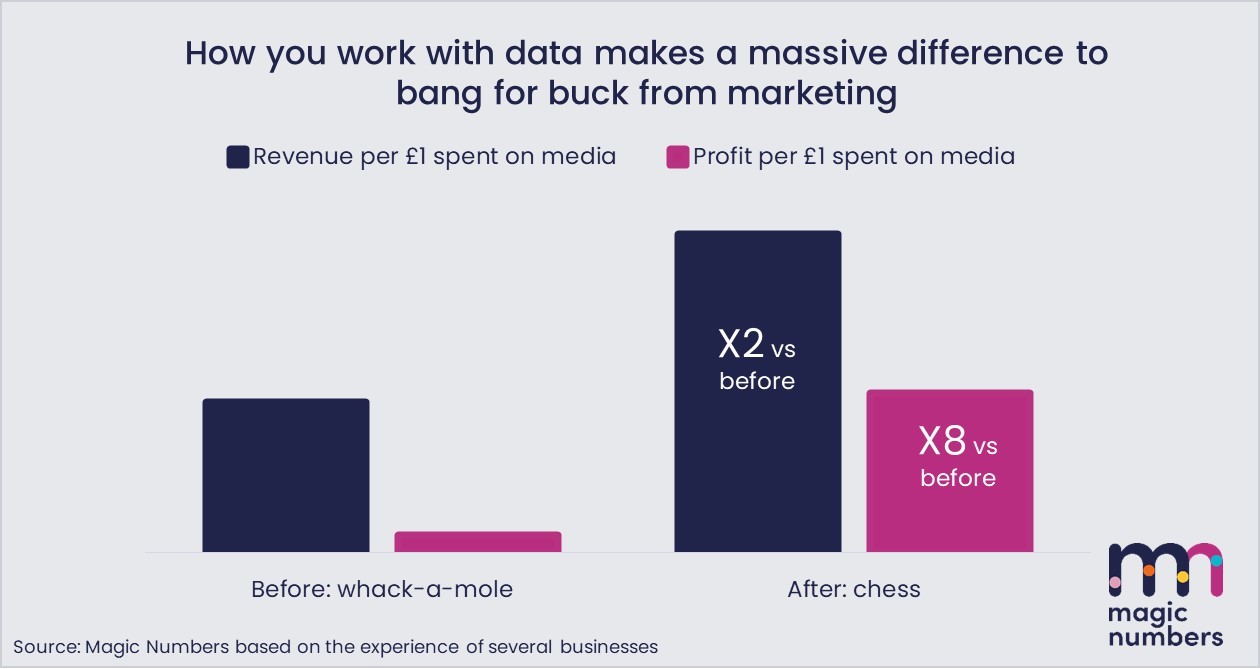

Despite all the frenetic activity and the best efforts of an increasingly frazzled team, the big picture numbers did not look good. Spend on Google and Meta was going up faster than sales, and profit margins were falling.

The online ad machine, just like the one in the arcade, took their money, but left them unsatisfied.

Whack-a-mole at work is stressful

It’s understandable why whack-a-mole has taken hold into marketing.

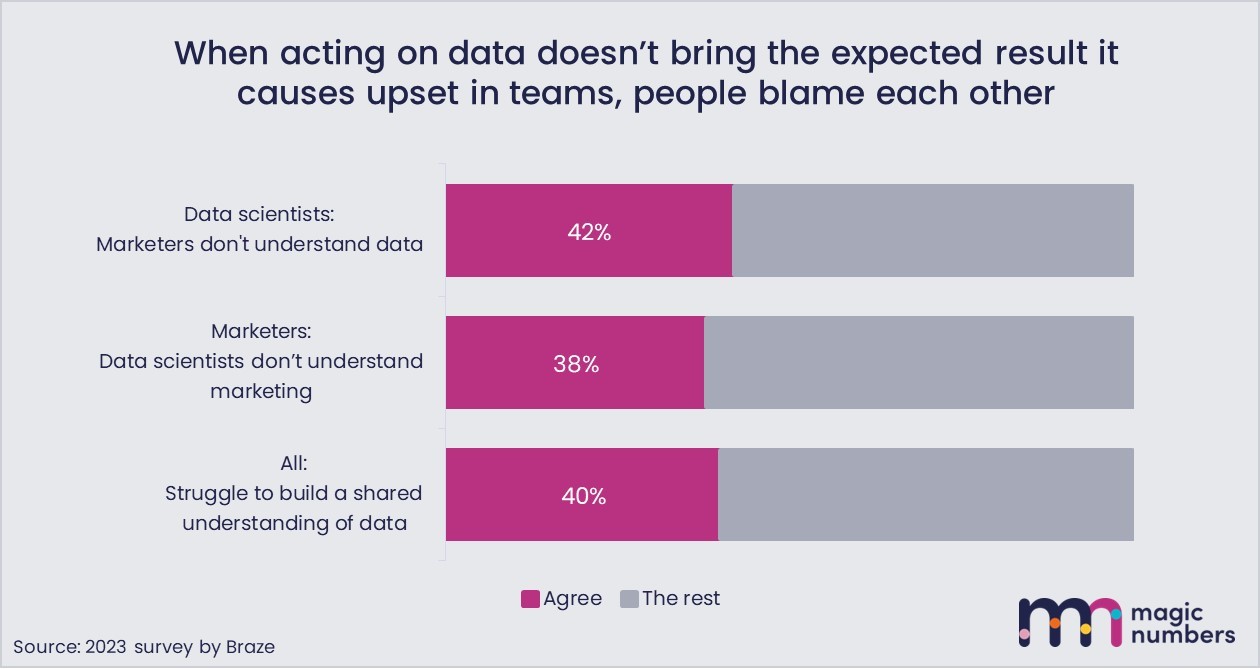

Senior people quite rightly want marketing to be numerate and accountable. So, marketing data scientists create reports and dashboards in good faith.

The trouble is that ups and downs in the metrics often don’t actually indicate ups and downs in how good your marketing is.